The funniest joke at the Edinburgh Fringe festival in 2016, as chosen by a panel of critics for Dave TV channel, was, ‘My dad suggested I register for a donor card, he’s a man after my own heart’ (told by Masai Graham). The first week of September is Organ Donation Week, an annual drive organised by NHS Blood and Transplant to promote the lifesaving potential of organ donation. Whilst the jokes of the Fringe and the NHS’s campaigns may not initially appear to have much in common, cultural representations –in comedy, novels, newspapers, and television – have played an important role in reflecting and shaping public debates around the medical, moral, legal and personal implications of organ donation.

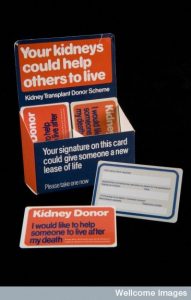

Organ donation has a long history. Whilst there are accounts of skin transplantation dating back as early as the second century, transplants of other organs were not documented until the early twentieth century, alongside improvements in blood transfusions. Through time, and particularly from the 1940s, surgeons developed their understanding of why certain organs were rejected, and developed immunosuppressive drugs to prevent this. The NHS’s website writes that the organisation has been ‘at the forefront’ of transplant technology since its own inception in 1948, with the first NHS kidney transplant in 1960, and the first NHS heart and liver transplants in 1968. The NHS established its first organ donor card, initially just for kidneys, in 1971, and the national organ donor database was created in 1994. In 2016, we continue to see medical innovation in transplant surgery (for example as surgeons transplant organs between donors and recipients who are HIV-positive). We also see controversial cases of medical waste, with donor organs in America sometimes thrown away due to an inefficient donor matching system, or weekend under-staffing.

As organ donation bec ame more common from the 1980s and 1990s, newspapers and factual television programmes paid attention. In 1985, the BBC consumer programme That’s Life!, presented by Esther Rantzen, appealed for a donor liver for the sick child Benjamin Hardwick. A liver was donated, and Ben became the youngest liver transplant patient. The programme also raised £150,000 from viewers and, contemporary newspapers speculated, contributed to a cultural shift empowering parents and clinicians to discuss paediatric organ transplantation. Echoing this line of thought, in 2014 Matthew Whittaker, who received a liver transplant in 1984 aged 10, told the Daily Mail that ‘I’m 41, but my liver is just turning 30. . . and it’s all thanks to Esther’.

ame more common from the 1980s and 1990s, newspapers and factual television programmes paid attention. In 1985, the BBC consumer programme That’s Life!, presented by Esther Rantzen, appealed for a donor liver for the sick child Benjamin Hardwick. A liver was donated, and Ben became the youngest liver transplant patient. The programme also raised £150,000 from viewers and, contemporary newspapers speculated, contributed to a cultural shift empowering parents and clinicians to discuss paediatric organ transplantation. Echoing this line of thought, in 2014 Matthew Whittaker, who received a liver transplant in 1984 aged 10, told the Daily Mail that ‘I’m 41, but my liver is just turning 30. . . and it’s all thanks to Esther’.

The close relationship between media and medicine was criticised at the time in the Guardian, arguing that journalists had become ‘recruitment officials for organ donors’, and should return to their role as ‘devil’s advocate[s]’, analysing medical research findings and government health policy. Some newspaper coverage did operate in this critical manner, however, for example investigative journalism exposing an organ trade between Britain and less affluent nations in the 1980s and 1990s. In one distributing example of this practice, in 1994 The Sunday Times reported that people from Bombay and Madras were selling their organs to British patients for as little as £200, making the ‘middlemen’ organising these deals up to £12,000 per operation.

Films, novels, and television programmes have also invited the public to think about the ethical, legal and personal implications of organ donation. The film Return to Me (2000) raises issues about identity, emotion, and transplantation, as a man falls in love with a woman who received the heart of his deceased wife. Similar debates were raised by media coverage around Jeni Stephien in August 2016, who was walked down the aisle by a man who had had her father’s heart transplanted years before, and told assembled media that, ‘It was just like having my dad here, and better’. Debates about informed consent, and emotional repercussions for donors’ relatives, were also played out in the Mills & Boon novel On Wings of Love (2013), where a transplant nurse falls in love with a grieving widower. In the American film John Q (2002), a desperate man with inadequate health insurance holds clinicians hostage in a hospital, forcing them to give his son a heart transplant. This raises questions about the responsibilities of the state in relation to organ transplantation – also discussed in Britain in relation to immuno-suppressive drugs, which recipients of organ transplants have had to pay for themselves.

These fictional representations likely invited reflection amongst viewers. Television producers have also explicitly sought to engender such debate. In 2005, a Casualty/Holby City crossover special asked viewers to vote to determine the outcome of an organ donation-related storyline. 98,800 viewers called, with 65 per cent voting that a heart donation should be received by Lucy, a young cystic fibrosis patient, over Tony, an older widower. Demonstrating an entwinement between fact and fiction, the programme also featured an informative section presented by Robert Winston explaining the guidelines governing organ donation.

Cultural representations of transplants can encourage us to think through our positions in relation to organ donation, and to discuss these with friends and family. A study of 1993 also found that when transplants were featured in newspapers and on television, this made it easier for intensive care professionals to raise the subject of organ donation with grieving relatives. Cultural representations of transplants can also have a negative effect on discussion, however. In 2013 the NHS Blood and Transplant group criticised the portrayal of organ donation in an episode of Holby City as ‘inexcusable and reckless’, for representing clinicians treating grieving relatives with ‘callous disregard’. Demonstrating the real effect of television, the Blood and Transplant group also stated they had been contacted by many people who wanted to be removed from the Organ Donor Register, as a direct result of this programme.

Newspaper articles, television programmes, even junky American films and Mills & Boon books, have all shaped how and when we think and speak about organ donation, by framing and highlighting issues such as consent, emotion, and bodily autonomy in particular ways.

JC

Should you wish to remove a comment you have made, please contact us

For your information and accuracy, organ donor recipients do not have to pay for their immuno-suppressive drugs. The hospital who provides their care arranges delivery of these drugs, every 3 months or so, byHealthcare at Home. At least this is what happens for renal care in the Derby area. However my husband does have to pay for his other prescribed medication as he is of working age.

This is useful information, thank you – I will look further in to this and modify the piece accordingly. Thank you for sharing!

All the best,

Jenny