Roberta Bivins

2015 seems a long time ago now – in these pandemic times, almost a lost world. Yet that was when the ‘People’s History of the NHS’ began, enmeshed in a research project funded by the Wellcome Trust to explore the cultural (rather than the political) history of the British National Health Service. Now the project has ended, several of us wanted to take a moment to think about what we have learned and experienced over the years we have worked together. Our shared goal when we launched the ‘People’s History of the NHS’ website was to ensure that our NHS history – the stories we in the team write about the NHS, but also our collective national experiences of life with the National Health Service since 1948 – would be shaped by the people who have made and lived the NHS: patients, practitioners, staff, activists and the general public. That is why we have been asking not just for your amazing, revealing, and sometimes disturbing stories, but also for your questions and ideas. You have shared them with us generously, both online and through our programme of community events and Roadshows.

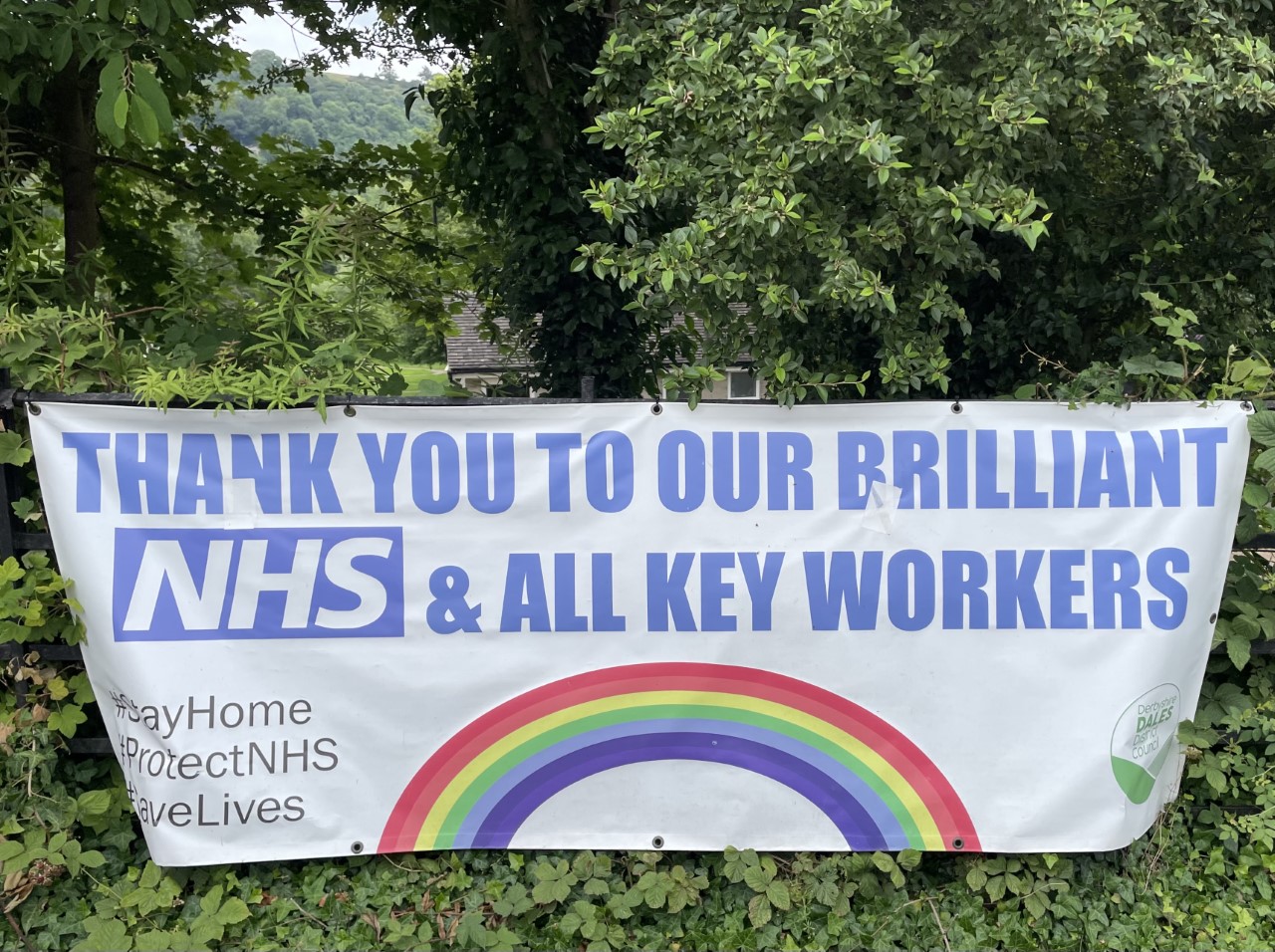

As a result, we have been able to curate a history that reflects perhaps our most important finding: the degree to which this national institution, now past its 73rd birthday, has become integrated into the life of the nations that make up the United Kingdom. For many, we have found that the NHS represents the best of what it means to be ‘British’, and symbolizes values that we aspire to enact – egalitarianism, inclusiveness, respect, and compassion –even though we may fail as individuals and a nation to deliver on them completely. Completing our project in Covid times, we as a nation (and as four nations) have seen the NHS in extremis, and as individuals have relied on it perhaps more than ever before. Responses to the pandemic have confirmed and amplified the symbolic power that the National Health Service exerts, but also the dangers that come with shared NHS narratives of exceptionalism and heroism.

These stories place heavy, even unbearable burdens especially on NHS workers, but also on each of us as we strive (sometimes unsuccessfully) to live up to demands that we can, somehow, take responsibility for a system deeply embedded in wider social inequalities in order to ‘Save the NHS’. But they are not new to our present times. The NHS began in desperate and dangerous times, and the rhetoric of its early years, too, was steeped in calls for staff to come forward to serve the nation, and for the public to use ‘their new health services’ responsibly: to refrain from using services and making demands as a way of protecting the infant NHS.

Indeed, the story of the NHS has all too often been written in the strident tones of crisis – sometimes, as with Covid, utterly genuine; sometimes confected for political or economic gain. So we are glad that our Encyclopaedia of the NHS, our NHS Virtual Museum Galleries, blogs, and most of all, your stories show us the NHS everyday. For good and for ill, in emergencies and in normal times, it seems, the NHS shapes our lives. Britain’s largest workforce, its most diverse, reaching into every community and every home, the NHS is also international: from 1948 until today it has been staffed by and has served people from around the world. For me, as an immigrant, this is almost as miraculous as the fact that here in the UK, we can see in practice what is elsewhere often just an ideal: the provision of healthcare as a human right, not a commodity.

Natalie Mann

Reflecting on the Cultural History of the NHS project at this present moment is a very strange and unsettling experience. The ‘Cultural History of the NHS’ project highlighted the absence of any work or research that tried to fully understand what the NHS means to the UK public beyond the delivery of healthcare and health services, and the roots of its socio-political history. There was a felt need to really get to grips with how the NHS began; not only as a welfare institution, but also as a cultural phenomenon, as a marker of national identity, values and principles. Looking back to its beginnings we also explored how the meaning and identity of the NHS as a cultural phenomenon had changed and developed over time. The landmark then was the NHS’s 70-year anniversary that was at that point on the horizon. This was a time for reflection and celebration. Politics as always gravitated to that historical nexus, with genuine anxiety around the very survival of the NHS. Now, however, we face an even greater challenge of taking stock. As Covid-19 swept across the UK the NHS and its workforce were put in the centre of the maelstrom. More than ever the critical and emotional value of the NHS was brought home in a way that outstripped platitudes and tired cliché. For the work and research that I undertook on the project the role of the NHS has impacted on and developed my previous thoughts and findings. A fundamental part of the project included the delivery of a 3-year public engagement strategy, where regular events across the UK consulted and worked with the public to find out what the NHS means to them, and in fact ‘how’ it means to them (through culture platforms such as TV, Literature and activism). Many of the responses were impassioned, some dejected, some even apathetic. I hazard a guess that re-visiting those questions now in consultation with the public would draw out if not very different responses, then at least a difference in urgency, tone and intensity. The project also took my work as a practicing visual artist into new territory. Previously having worked on projects around homelessness, addiction and child poverty, during my time on the project I developed a proposal for a visual piece of work that looked specifically at NHS uniforms – in particular nurse’s uniforms – as markers of status, morality and belonging (in part driven by the autobiographical ambient sound of my own mother sewing nurse’s aprons on an industrial sewing machine in the bedroom of our Black Country council house). Faced with the calamity of PPE during Covid, this is a project I have picked back up and intend to take forward with a different layer of visual meaning. As the project website emphasises, this was always a People’s history; my role on the project was to bring those histories to the fore. The gap between a 70-year anniversary and the global sweep of an international pandemic, between the project’s start and its end, almost feels like a chasm reflecting from this historical moment. More than anything, however, it reveals how important that work was, is, and how much still remains to be done.

Rosemary Cresswell

Joining the project in November 2020 meant having too few opportunities to meet with Roberta and Mathew in person because of the lockdown, and missing out on many of the fabulous public engagement opportunities which the project team had previously undertaken. However, Roberta had the great idea of using the ‘voices’ from the People’s History of the NHS website to create a graphic novel. I was tasked with finding an artist; Darryl Cunningham, author of Psychiatric Tales (2010) and Science Tales (2013), proved to be a perfect collaborator for our project. Over the years of the Cultural History of the NHS project, staff and patients had submitted more than a hundred stories to the members’ pages of the website providing a rich resource for personal perspectives of NHS history. This was coupled with material already in the public domain and research from the wider project to provide a fuller picture. Curating the stories submitted to the webpage meant reading a combination of both happy and very unsettling memories, and collating them under different themes. Darryl was sympathetically able to use selected stories to provide contrasting ‘voices’ of the experience of working within and being cared for in various situations within the NHS healthcare system, and Roberta and I communicated with many of the authors about the inclusion of their stories.

My role also included updating the project website and twitter, and I hosted a seminar featuring Gareth Millward (University of Warwick) and Stephanie Snow (University of Manchester), discussing ‘Present and Past’ experiences of vaccination campaigns. The seminar was in response to both the COVID pandemic and to the large number of comments discussing the website’s encyclopaedia entry on childhood vaccination programmes. Along with working on the public engagement side of the project, I was also involved in assisting with research topics varying from novels, television series and films to private medicine within and outside of NHS settings.

Dr Rosemary Cresswell, project research fellow between November 2020 and June 2021, and now at the School of Social Work and Social Policy at the University of Strathclyde.