By Hannah J. Elizabeth on World AIDS Day, 2020

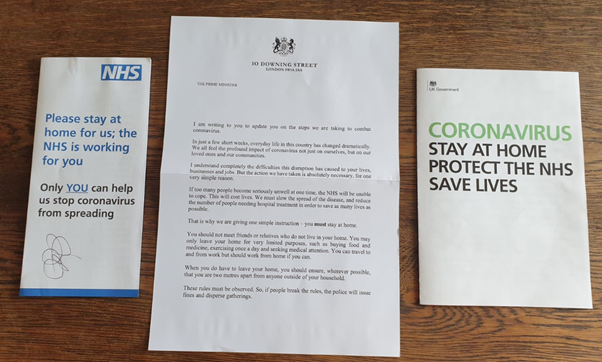

A couple of months ago, many households in England and Wales received a letter, ostensibly from Boris Johnson, explaining the public health crisis COVID-19 represented. The letter and leaflet told us what we could do to keep ourselves (and the NHS) safe. Below are photos of the letter and (Birmingham specific) leaflet I received (hence the scribble on the leaflet where I thoughtlessly checked if a pen was working).

(For larger images, please see our gallery)

Decades ago, something similar happened under a different Conservative government. We – and by we, I mean every household in Britain – were sent a letter in the post concerning AIDS by the Department of Health and Social Security.

Of course, we cannot usefully compare HIV and Covid-19 as viruses: they are too different both biologically and culturally. However, both were seen as novel threats, triggering largescale health crises which forced urgent government responses. Here, I’m interested in thinking critically about the stories these campaigns tell us about our place as individuals and members of a collective, and the presence or absence of the NHS as a talisman/vessel for local community responses and feelings.

Getting a letter from the government about a public health issue creates a different experience from seeing a poster on the underground or in a GP’s waiting room. A leaflet which is sent to us individually feels more personal and less ‘optional’ than one we pick up from a packed shelf while we sit bored waiting to be seen by a nurse.

This personal and individualising touch is deliberate, and falls in line with the messaging we see in both these campaigns.

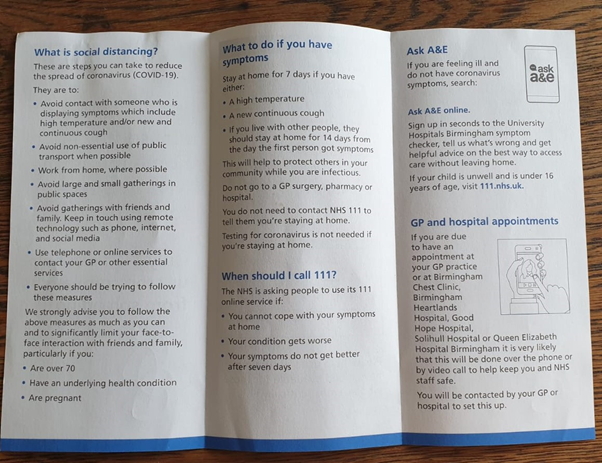

Please stay at home for us; the NHS is working for you. Only YOU can stop the coronavirus from spreading.

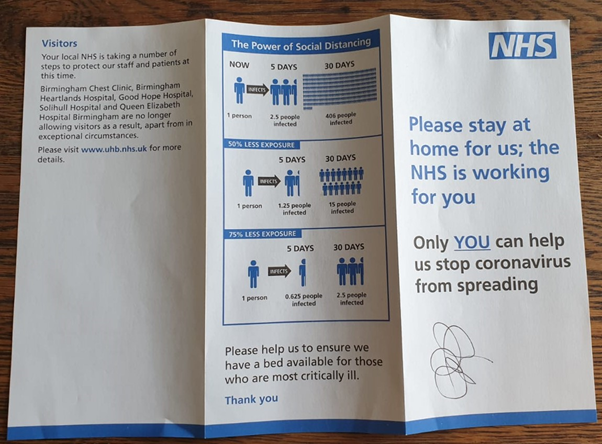

With COVID-19, the message relies on the plea to protect others, here presented as a collective, common sense ‘us’ – only the semi-colon hints that we might want to think about who that ‘us’ encompasses. ‘Us’, it transpires, is the NHS, but is it also a greater collective of the British people? All ambiguity is done away with in the next line when we are told ‘Only YOU can stop the coronavirus from spreading’ imputing a personal onus on the individual to protect the collective.

In contrast, the ‘Don’t die of ignorance’ campaign’s focus remained almost entirely on individual rather than collective peril. While readers are encouraged to ‘make sure everyone who may need this advice reads this leaflet’ the emphasis on talking to ‘children’ makes evident the assumption that the leaflet will be deployed by individuals to protect themselves and their families specifically. While there is some mention of preventing a wider spread of the virus by ‘all taking precautions’, the emphasis on personal ignorance, leading to discouraged behaviours, resulting in personal risk and perhaps death, somewhat drowned out these broader appeals. This is only amplified by the threating slogan and imagery which were hallmarks of the campaign of which this rather more measured leaflet was an element.

Indeed, much can be gleaned by merely comparing the slogans of these two health campaigns. ‘Don’t die of ignorance’ was part of the ‘Don’t aid AIDS’ campaign. Crucially, the latter slogan laid blame for the spread of the virus at the feet of individuals who failed to act according to the protective knowledge made available to them through the campaign. In contrast, ‘Stay at Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives’ – moves optimistically from specific achievable individual action, to admirable consequences: protecting the NHS and the innumerable unknown lives which will be saved. Indeed, while the ‘Don’t aid AIDS’ campaign worked hard to conjure a sense of individual risk and culpability in order to persuade members of the public to change their behaviour, ‘Stay Home; protect the NHS; save lives’ operates on/invokes a sense of collective risk to persuade us all to change our behaviour to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Hannah J. Elizabeth

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

Should you wish to remove a comment you have made, please contact us

With falling GP morale, the negotiations on the Charter for General Practice provide financial incentives for practice development, plus substantial rewards. A milestone in defining the role of general medical services, the 1966 GP contract addresses major grievances of GPs and provides for better-equipped and better-staffed premises, greater practitioner autonomy, a minimum income guarantee, and pension provisions.