By Laura Carter, University of Cambridge, @carter740

Laura is a postdoctoral researcher on the ESRC-funded project ‘Secondary education and social change in the UK since 1945’, you can view their website here.

This summer Chris Jeppesen and I have begun working in the archives of the 1958 and 1946 British birth cohort studies, respectively. This involves us collecting qualitative information from the original questionnaires of these studies, especially from the school-age ‘sweeps’, for a sample of 150 individuals. I won’t go into the details of how we constructed our samples here (that’s for another post) but we are subsequently combining this newly-mined qualitative material with existing quantitative data on factors such as social mobility, region, and family status to create mini life-stories, or pen portraits, of each person in our samples.

The best part of this research is by far the original questionnaires. Each individual ‘sweep’ (the term used to describe the data collection exercise of interviewing, examining, or sending out a postal questionnaire to the survey members) may only contain a few pockets of qualitative information, maybe one or two questions begging for a two-line answer such as ‘If you had your time again, what age would you leave school and what training would you do?’. But when accumulated across the life course and seen alongside hard ‘facts’ such as school-leaving age and occupational status, you can obtain a very textured picture of these twentieth-century lives.

Whilst still in the middle of this research, last week the SESC team attended the conference ‘Cultural Histories of National Healthcare’ at the University of Warwick. This conference was hosted by the Wellcome-Trust funded ‘People’s History of the NHS’, a project similar in scope and ambition to ours, exploring another cornerstone of Britain’s post-1945 welfare state. Our PI, Peter Mandler, gave a paper about the sometimes convergent and sometimes divergent trajectories of health and education as universal services in the postwar period. This comparative lens was ideal for a conference that was very successful overall at putting all aspects of the NHS in their wider social and cultural contexts.

One of the most interesting topics raised in discussion was the spectre of the 1930s in early assessments of the shiny new services of the immediate postwar years. In both cases, the working-class parents and patients of the 1940s and 1950s had experienced limited, means-tested services before the war, whilst middle-class parents and doctors had reasons to hark back to the virtues of voluntary hospitals and interwar Grammar schools. Another theme was the use of languages of discipline and control in the early NHS, both directed towards patients and in the workforce. It was noted that this is not a common discourse used in relation to the Health Service, whilst in histories of education the work of 1960s sociologists, especially at Birmingham’s CCS, established an influential analysis of schools as sites of social control, where ‘working-class kids found working-class jobs.’[1]

This break to visit Warwick naturally prompted some further co-mingling of thoughts on the histories of health and education once I returned to the 1946 cohort archive the following day. The 1946 British birth cohort study, formally known as the National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD), was (and is), after all, a medical study. The questionnaires I am reading from the late 1950s ask about schooling on one page and hospital visits on the next, and the sweeps of the late 1960s ask about maternity care and in-work training in quick succession. As Sian Pooley’s recent work explores, such surveys are documentary evidence of ordinary people learning to use these new services, sometimes imperfectly. I have already seen a few parents in 1954 answer the question ‘What type of school would you like your child to go to?’ with the answer: ‘Grammar school, if we can afford it’. The interviews with each child’s mother, carried out up to 1961 when the study members were aged 15 and usually on the brink of leaving school, were conducted by either school nurses or health visitors. The NSHD, as an historical phenomenon, was a collection of multifarious state-expert-citizen interactions that was only possible because of the sheer reach of the two new universal state services of the NHS and compulsory secondary education.

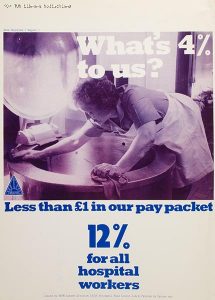

In his presentation on the NHS’s workforce at Warwick, Jack Saunders suggested that NHS nurses had ‘ambiguous class identities.’ The idea that nursing wasa site of particular social mobility for working-class girls was explored further in the Q&A, and it made me want to highlight how nursing has featured in some of the NSHD lives I have been uncovering. The entire 1946 cohort undoubtedly experienced unprecedented social mobility, largely through the labour market rather than education, but the structural barriers facing women born in 1946 and seeking to ‘get on’ should not be underestimated. Nursing was a common aspiration for working-class girls (and their parents) in the 1950s, a ‘respectable’ job that adhered to gender norms. And thanks to the expansion prompted by the NHS, it could be accessed without school-leaving qualifications, and therefore without a Grammar school education, for almost the entire postwar period. Our project will use sociological sources to add layers of social and cultural experience to the existing, quantitative picture of social mobility, so understanding the educational making of nurses’ ‘ambiguous class identities’ is our bread and butter.

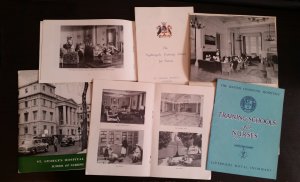

In 1962 – the year that 1946 cohort members left school if they attempted ‘O’ levels – full-time nurses and midwives made up 32.4% of the NHS workforce, the second-largest group behind domestic and maintenance workers.[2] Training to become a nurse in the 1960s meant applying to a nursing school, where you were likely to live-in and have an active social and working life while you trained. Decisions on where to train might be based on distance from home, or an estimation of the institution itself, with the more prestigious teaching hospitals offering more chances for progression to senior roles. There is a brilliant gallery of 1960s nursing school prospectuses illustrating these settings on the ‘People’s History of the NHS’ website Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

In 1948 the role of State Enrolled Nurse (SEN) was introduced, which required two years training and was a less senior position than the State Registered Nurse (SRN). It was also still possible to become an Auxiliary Nurse with no training. Following a drive towards professionalization by the Royal College of Nursing, the first nursing degree was established in 1972. Jack Saunders explains these changes in his excellent blog post on student nurses, and also explores the ongoing dispute over the status of ‘student nurses’, since the study period for SENs and SRNs always involved grueling work schedules.

Such decisions about training and status can certainly be seen in the NSHD sources. At age 13, several girls in my sample stated that they wanted to be a nurse, usually mentioning fondness for small children, an affinity to service, or empathy for the sick. Parents who wanted their 15-year old daughters to become nurses most often cited temperament as the reason. But the types of girls who actually followed these aspirations through are particularly revealing, two of which I will explore in detail in the rest of this post.

It is first important to note that the NSHD only followed babies born in Britain in 1946, before mass Commonwealth immigration, and collected no ethnic data. It did not include Northern Irish nor, obviously, Irish participants. It is therefore not possible to use my sources to explore the educational pathways of the tens of thousands of women of colour who migrated to Britain to work as nurses from the 1950s or of the equally significant influx of Irish nurses who took up Auxiliary roles, and whose experiences must remain central to our wider picture of work in the NHS. The 1971 ‘Briggs Report’ on nursing stated that nurses and midwives from ‘developing countries’ made up 8% of the staff in acute hospitals, 11% in psychiatric hospitals, and 8% in other hospitals across Britain, focused in England and even more so in London.[3] No comparative figures are given for Irish nurses. After three decades of active NHS recruitment of low-skilled health workers to emigrate, particularly in the Caribbean, by the late 1970s 12% of the student nurse and midwife population in Britain came from overseas.[4]

Vivienne

Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

Vivienne grew up in a working-class family in Yorkshire. Her parents stated nursing as their aspiration for her career when she was aged 11 and they wanted her to go to a Grammar school. In the end, she went to a Secondary Modern school, still stating nursing as her career choice at age 15 and writing ‘I would like to work in a hospital and if possible when I am fully qualified, accompany a doctor who is helping the people abroad’. The opportunity to take GCEs (or ‘O’ levels) was by no means a given in secondary modern schools in the early 1960s, but Viv stayed on beyond the minimum school leaving age of 15 to do so. Vivienne achieved school honours and played in school sports teams, but her teachers noticed a shift in her attitude in her fifth year: ‘she became giggly and appeared at times rude and ‘don’t care’’. She had gone off the idea of nursing by the following year, ending up leaving school a few months before her seventeenth birthday with only two GCE passes, even after some autumn retakes.

Viv worked in a laboratory locally for few years before deciding to try for nursing again in 1964. Looking back in 1968, she regretted this period and wished she had gone straight into training for Sick Children’s Nursing. But by this time, she was also married and stated that she found ‘working full-time at the Hospital, and looking after my husband and home, too much for me.’ She chose to start working part time, and by age 26 was a Staff Nurse (SRN) on a Children’s Ward and had hopes for a baby in the future. A strong supporter of the Labour Party (although she couldn’t vote for Harold Wilson in 1970 because of her shift work), her attitudes to social class in her mid-20s were clear cut. She felt that different classes were distinguished by ‘those who had money and those who did not’, and saw herself as working class because she was working for a living. By mid-life, Vivienne had climbed the social class scale by four steps.

Daphne

Daphne grew up in a large Roman Catholic, staunchly-Labour voting, working-class family in County Durham. She succeeded in gaining a place at a girls’ Grammar school (Roman Catholic) and neither her nor her parents mentioned nursing as an aspiration until she was aged 15, at that point both mentioning her desire to nurse small children. At secondary school Daph’s teachers considered her a lazy or poor worker, with little or no power of concentration, and who was sometimes disobedient and difficult to discipline. She tried for some GCEs but failed all of them, and her parents at that point decided she should leave school at 16 and take a job as a bank clerk. In the mid-1960s, Daphne dabbled in a shorthand typing course and told the Survey that she wanted a career in commercial art. But in 1966 she left her office job to work as an Auxiliary Nurse, and then begun training to become an SRN a few months later.

Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

At age 22, although she wished she had started her nursing training sooner, she also reflected that she would not have been able to commence until 18 because of the need to help support her family home. In her early to mid-20s, Daphne’s main work-related complaints were about her wages: ‘…which I think are not very good for a 22yr old girl working a 42 hour week, as I buy most of my uniform and pay 2/6d bus fare every day.’ Prefiguring the low-pay campaigns in the NHS that were to characterise the 1970s, Daph noted that she was greatly looking forward to a promised 20% pay rise in 1970 for all SRNs. At age 26 she was still working as an SRN on an orthopaedic ward and remained living at home with her parents. She hoped for ‘a really secure post, say a sisters post in an orthopaedic hospital’ and also said that ‘I suppose I would like to marry if I met the right person, but at the moment I feel that my job comes first & is more important.’ Like Vivienne, when asked about her attitudes to social class in 1972, Daphne saw class as a material rather than cultural difference: ‘To me it’s really a question of money. It’s certainly not the people themselves it’s what they’ve got behind them in capital.’ At mid-life, her social class status was three steps higher than at childhood.

***

Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

In some ways Vivienne and Daphne’s educational trajectories are similar to many of the other women I have looked at, with lots of chopping and changing in the first few years of the labour market and a limited set of career options without school-leaving qualifications. And there is nothing remarkable in the fact that both Viv and Daph experienced considerable social mobility in quantifiable terms but neither perceived that their working-class identities had changed at all during this process, a phenomenon explored in Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite’s new book. They differ from many, however, because they continued to work after marriage or delayed marriage for their career (the average age for women to marry in 1966-7 was at its lowest in the postwar period, at 21).[5] Notably, these two women and all of the other nurses in my sample at least attempted some form of school-leaving qualification before leaving school, regardless of the type of school they attended (by 1970-71 it was still true that most trainee nurses had no such qualifications; only 11% entered with two or more ‘O’ level passes).[6] This is, I think, where the educational and cultural motors behind those ‘ambiguous class identities’ start to show.

For all my nurses, nursing was a girlhood school aspiration that they returned to after not marrying young (for whatever reason) and after facing the harsh reality of the lack of progression available in other workplaces for women with little or no formal qualifications. As their working lives progressed, they retained a strong vocational commitment to nursing, despite the financial and family life impracticalities that hospital work entailed. It was also a career, something related to an identity outside of being a wife and mother, which promised a form of professional status that was still very difficult for women from working-class backgrounds to obtain in Britain until much later in the century when access to university was widened.

Photograph taken from the private collection of Anna Page, courtesy of George Gosling.

So often in stories of the leap from childhood career aspiration to adulthood fulfilment or disappointment, secondary education is presented in stark terms as simply good or bad, enabling or obstructive. The case of nursing reveals the ambiguity of experience and highlights the importance of the early years in the labour market for the first postwar generation who were able to obtain a secondary education and work in the NHS. It is a mark of how far women’s work drove social change in the postwar period that girls born just twelve years later, with an interest in the medical profession, could so triumphantly ditch the gendered discourse of nursing of the ‘46ers and aspire to a career as a doctor, as explained in this year’s Daily Mail celebration of the National Child Development Study at age 60. Likewise, recent research from the Millennium Cohort Study has found that girls from all ethnic groups apart from white aspired to be doctors when they grew up.

The support of the Economic and Social Research Council and the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health & Ageing are gratefully acknowledged.

[1] Paul Willis, Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs (1977).

[2] Staff numbers NHS England & Wales, 1962.

[3] Report of the Committee on Nursing (HMSO, 1972), p. 26.

[4] Stephanie Snow and Emma Jones, ‘Immigration and the National Health Service: putting history to the forefront’, History & Policy, 8 March 2011.

[5] Carol Dyhouse, Students: A Gendered History (2006) pp. 92-3.

[6] Report of the Committee on Nursing (HMSO, 1972), p. 59.

Should you wish to remove a comment you have made, please contact us

Thanks for finally talking about >Viv and

Daph’s educational roads to nursing: reflections on the history of secondary educafion and the history of the NHS

– People’s History of the NHS <Liked it!