This provocative question – what would a Museum of the NHS look like? – is one which we have asked at public events and meetings throughout our research project. We think it is a question which is deeply revealing of attitudes towards the NHS, and changing beliefs about its meaning, cultural value, and everyday place in people’s lives. Yesterday we asked this question to a brilliant group of students participating in a Sutton Trust Summer school at the University of Warwick, where they were studying ‘objects with agency’ and in a short workshop convened by Professor Mathew Thomson. Not to get all Buzzfeed on you, but their answers did amaze and impress us!

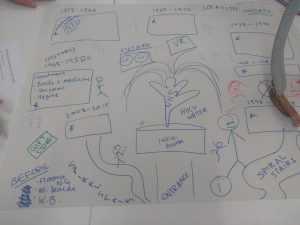

Placed in to four groups, the students responded to this question with remarkable open-mindedness, enthusiasm, and creativity. The pictures which they drew – reproduced with their permission throughout this blog – gave us so many ideas for a new Museum, if anyone reading has this kind of cash available…? Student answers also helped us to think about how young people think about the NHS, an important question for our research which often confronts the idea of a generational divide in attitudes to healthcare.

Interestingly for us, the students’ lovely pictures revealed that they already had significant factual knowledge of NHS history. Two of the Museums featured statues of Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health when the service was founded, demonstrative of the important place of this founder-politician in national and cultural memory. The students’ drawings also revealed an interest in this history and in breaking down chronology: while most Museums were ordered chronologically, not all were, and indeed the chronological Museums were organised differently, one by decade as ‘1940s’, ‘1950s’, etc and one from 1948-1958, 1958-1968, etc. The students interest in history was entwined with concern about the future of the NHS, and two of the Museums had spaces where members of the public would debate this. Another Museum featured a space to discuss ‘current affairs’, and plans to acquire the famous ‘Brexit Bus’ promising £350m per week to the NHS…

Pleasingly for us, students were also interested in the NHS in culture, and one Museum featured a screening room which would show documentaries about the NHS, as well as popular television shows such as Casualty and 24 hours in A&E. Students also thought of the perception of the NHS as a miracle-worker, and one Museum centred around a fountain of holy water, testament to the progress of modern medicine today. Looking closely at these images further shows that the students grappled with key questions of our project: by placing galleries looking at vaccinations, surgery, and drugs alongside those looking at ‘personal stories’, they explored how medicine relates to the NHS, and how individual experiences shape our thinking of national institutions. Students also placed the everyday and mundane parts of medicine – such as glasses, uniforms, teeth, and nursing homes – alongside famed politicians and surgical innovations, reflecting our interest in how the everyday is inflected by, and powerful in, the political. Three of the four Museums that the students created made special space to assess women’s health and women’s medicine, reflecting, again, our research interests in the limitations and reach of this ‘universal’ Service.

The students discussed the idea that the NHS was not merely hospital buildings, but rather a feeling, or sense of public ownership, and one Museum was shaped like a ‘U’, because ‘the NHS belongs to us’. Another was shaped like the letters ‘NHS’, and indeed the students were interested and surprised to learn that our specific NHS branding was only invented in the late-1990s. Interactive spaces were a common theme in these Museums, which was both a reflection of shifts towards Museums as participatory spaces but also seen to reflect an idea of public and patient involvement and investment in the health service. Students portrayed common features of Museum life – such as gift shops and cafes – but also suggested innovative new types of layout, such as a womb slide to enter the Museum, which could then be laid out to reflect the life course, from ‘cradle to grave’.

Overall, working with these students has really inspired us! Their thinking about a Museum of the NHS was exciting and creative, and we need to think about whether we can use these ideas to redesign our Virtual Galleries. The students also had really interesting responses to the question of why there was not yet a Museum of the NHS, suggesting that the NHS was a Museum, that its TV and cultural representations were a Museum, that a Museum would be a waste of money, and indeed that a Museum may represent the end of the NHS, and its consignment to history (the latter response we also encountered at St Fagans Museum in Wales). In further exciting new knowledge, when we gave the students objects to analyse, they showed us that the 1950s prosthetic leg which we own, which we often take to public events, can bend at the knee! A physical shift we had never made before, and just one symbol of the ways in which these students challenged, enhanced, and broadened our thinking. We are very grateful for the opportunity to work with these brilliant young people, and are paging all wealthy philanthropists to make their Museums in to a reality asap!